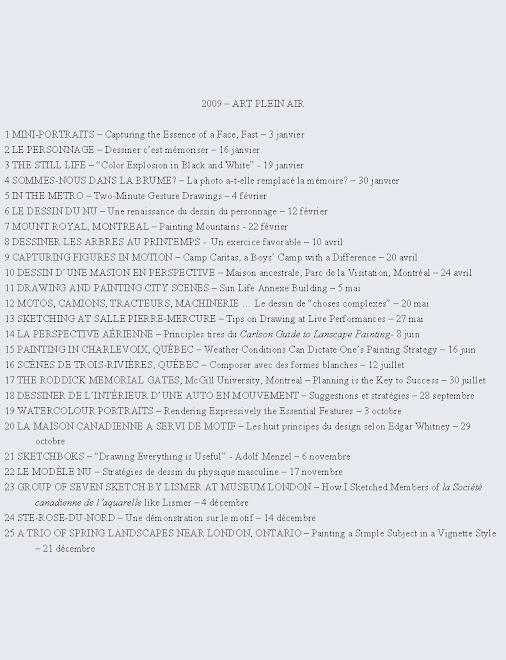

Peindre sur le motif

Le désavantage de la peinture sur le motif est que la lumière change très rapidement. Par contre la peinture en direct nous oblige à composer avec nos premières impressions et nos émotions. Donc, contrairement à la peinture uniquement d’après photo, nous devons peindre plus par intuition étant donné le peu de temps qui nous est alloué. Parce qu’elle est plus réfléchie, la peinture d’après photo peut parfois avoir l’allure d’une copie de la scène au lieu d’une interprétation.

Une démonstration

J’ai peint cette scène lors d’un atelier en plein air. La photo de la maison a été prise à titre de référence. Donc je ne m’y suis pas référée lors de la démonstration. Je l’ai peinte partiellement en direct et partiellement à l’intérieur, de mémoire. Le but de la démo était en partie de montrer comment on peut changer des éléments afin de personnaliser le sujet selon certains principes de composition.

Divers éléments modifiés selon les principes du design

Les huit principes du design - unité, conflit, dominance, répétition, alternance, balance, harmonie et gradation - tels que l’enseignant américain de renom, Edgar Whitney* les expliquait m’ont été utiles afin de modifier certains éléments :

1. Les fenêtres, les pierres et l’ombre portée : Je trouvais la disposition régulière des six fenêtres trop statique. J’ai donc alterné l’espacement entre elles et j’ai varié la largeur de certaines. J’ai décidé de rendre certaines pierres de la maison plus dominantes que d’autres. Une ombre portée sous la corniche a été ajoutée en imaginant un éclairage éblouissant pour amener une variation.

2. Les lucarnes, le ciel et l’arbre : Parce que le ciel, en cette journée, paraissait aussi blanc que les toits des lucarnes, ni un ni l’autre ne dominait. J’ai donc crée un conflit dans un ciel bleuté en introduisant des nuages. Le rebord blanc du toit et des lucarnes contrastent maintenant contre le ciel. J’ai alterné la valeur du feuillu de l’arbre de gauche tout en unifiant la masse.

3. Les arbres, l’arrière-plan et le gazon : Les verts se ressemblaient tous. J’ai donc alterné les verts en introduisant du bleu, du jaune et du brun dans le mélange en variant la quantité d’eau et de pigment dans mon pinceau. On remarque maintenant un conflit et un dégradé dans les verts.

4. L’avant-plan, le côté de la maison et le sapin : Le palier de gazon vert neutre et uniforme à l’avant empêchait une ouverture dans la scène. J’ai donc inventé des espacements en peignant en style « vignette ». Ceci a crée de l’unité. Les blancs du papier permettent maintenant l’entrée dans le tableau à divers endroits. J’ai peins le sapin de droite d’un vert très foncé devant une façade plus pâle et floue. Il y a maintenant un conflit favorable ainsi que de l’alternance, de la variété et de la dominance entre les arbres.

Soyez conscients de ces principes en conjonction avec les sept éléments du design – la ligne, les valeurs, la couleur, la texture, la forme, la grandeur et la direction – los de la «construction » de vos tableaux. Whitney disait que « les amateurs peignaient des tableaux, mais les professionnels bâtissaient des œuvres avec ces briques de connaissances. Ne pas s’en servir était semblable à un coup de dé.»

Bonne peinture en direct.

Raynald Murphy sca

* Learn Watercolor the Edgar Whitney Way par Ron Ranson