“There is a vast difference between drawing and making drawings. The things that you will do – over and over again – are but practice. They should represent to you only the result of an effort to study, the by-product of your mental and physical activity. Your progress is charted, not on paper, but in the increased knowledge with which you look at life around you.” Nicolaides in The Natural Way to Draw.

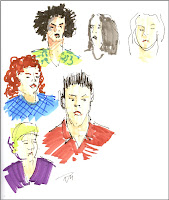

“There is a vast difference between drawing and making drawings. The things that you will do – over and over again – are but practice. They should represent to you only the result of an effort to study, the by-product of your mental and physical activity. Your progress is charted, not on paper, but in the increased knowledge with which you look at life around you.” Nicolaides in The Natural Way to Draw. On Tuesdays I attempt to develop my drawing skills by challenging myself. I make drawings in a moving subway car on my way to a life drawing session. (Visit my earlier blogs). Before arriving I might stop at a café and make more drawings of people. Again, drawing a shifting model can be frustrating but only if one worries about the resulting sketch. Another challenge is drawing the live model. Finally, arriving back home and trying to capture on paper the essence of a fleeting “camera shot” of a singer on the TV show American Idol can seem to be a formidable task.

Nicolades says there is a vast difference between drawing – doing a nice neat finished drawing for its own sake, or maybe even to exhibit - and making drawings. I agree. When I am making drawings I am studying what is around me and making exploratory marks on paper. I am also developing a skill and a system of graphic symbols. But most importantly I am doing so for myself, to learn. I am not afraid to make mistakes. As a matter of fact, trial and error is part of learning. Actually, if I am not making mistakes, I feel I am not progressing. I am just repeating myself, therefore not really learning.

Michael Merzenich, a leading neuroplastician, says : “…practicing a new skill, under the right conditions, can change hundreds of millions and possibly billions of the connections between the nerve cells in our brain maps… we can also change the very structure of the brain itself and increase its capacity to learn. Unlike a computer, the brain is constantly adapting itself.” (Quoted from The Brain That Changes Itself, by Norman Doidge, M.D.)

Just think of the possible billions of connections I am making in my brain while making drawings and enjoying the process while doing so!

So, the next time you are watching American Idol or a similar TV show, reach for your sketch book. Seize the opportunity to increase your knowledge of the human form. You will also be increasing your brain power! One can more easily draw from newscasts, talk shows, stand-up comedy and shows such as American or Canadian Idol. There are often close-up of people on these shows. Hosts and guests stand relatively still.

Technical note: The illustrated drawings were done in an 8 ½” x 11” sketch book using a variety of tools: graphite pencils, Nero soft pencils, Permanent Micron ink pens and permanent color COPIC markers.

Raynald Murphy sca

Version (2) 6 x 6 , papier Aquabee

Version (2) 6 x 6 , papier Aquabee